| SPECIFICATIONS | |

| Denomination | One Fanam |

| Metal XRF | Gold Au0.721 |

| Alloy | Ag%Cu 0.79 |

| Type | Struck |

| Diameter | 8. MM |

| Thickness | 1.06 MM |

| Weight | 0.39 gms |

| Shape | Round |

| Edge | Plain |

| DieAxis | O° |

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

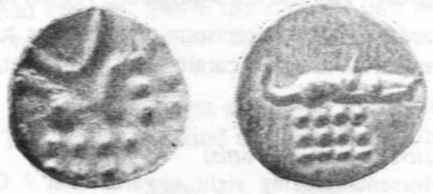

Obverse : Stylistic Lion (Sardula) standing right with large crescent above.

The legs represented by 2 rows, each of 4 dots. The lower 4 dots with downward

spikes. 4 more dots separated from this group to right. Concave surface

Reverse : Stylistic Boar standing right. The legs represented by the

3 rows, each of 4 dots. Convex surface.

The edge of the gold coin is 0.55 MM and 0.85 MM with raised design.

However the pronounced curvature gives it a total it 1.05 MM thickness.

| This gold fanam shown above was selected for this web-page by Alan VanArsdale to have a complete design and match as close as possible to Elliot pl. 4 #189; as illustrated on right. It is from a recently found hoard he had obtained from south India. A tested random sample of which was more than 75% pure gold. |

|

The 1886 Elliot description of his 189-192 Viraraya fanams as obv:(?): Transverse bar, sometimes with the end turned up, or simply elongated like a crocodile or saurin above three lines of dots and a reverse design not explained. He says The many varieties of gold fanams, through no longer current are found in considerable numbers, many of them having curious devices, without legends.

Note that this example is probably much more recent than the original Hoysalas fanam illustrated in Mitchiner. The animal figures are more stylistic. The angle between two sets of dots on the obverse in this example is much less than 90 degrees while it is more than that in the Hoysalas fanam. The two groups of dots in the obverse merge in the Viraraya fanam, to 2 arcs, each of 6 dots.

According to Elliot (page 148), small coins were measured or counted by means of a chakram board, a small square wooden plate with a given number of holes the exact size and depth of a chakram. A small handful of coins is thrown on the board, which is then shaken gently from side to side so as to cause a single chakram to fall into each cavity, and the surplus, if any swept off with the hand. A glance at the board, when filled, shows that it contains the exact number of coins for which it was intended. The rapid manipulation of this simple but ingenious implement requires some practice, but the Government clerks and native merchants are exceedingly expert and exact in its performance.

Text from

* 1998 Coinage and history of Southern India, vol. 2: TamilNadu - Kerala

Michael Mitchiner Page 252.

The gold fanam was scanned and displayed at 600dpi. It was purchased in 2000 December on the web from Alan Van Arsdale in USA who guarantees its authenticity.

Warning: Be careful when buying. Steve Album reported to the SouthAsia-Coins Egroup that South Indian gold fanams have been forged for decades, partly for distribution through promoters and telemarkers in North American and Europe, advertised as "the world's smallest gold coin". Many are good gold, but some are just gold-washed base metal. Many tens of thousands were distributed around the US by a Florida dealer (now deceased) in the 1970s and 1980s. The fakes were probably made to order in India. The design on those fanams frequently seen on ebay is clearly different from the fanam shown on this page.

Elliot calls the side with 3 rows of 4 dots which is convex in the

above example the obverse, different from both Mitchiner and

Codrington who call it the reverse.

John Deyell

replies

that since the obverse or head has a convex surface and is in

general a more finely engraved portrait which is put on the lower

Anvil-side since that is less likely to damage. The reverse or tail

side has a concave surface and typically show more die variety since

the upper hammer-side absorbs more of the shock.

The Indians followed this Greek minting tradition.